Friday, March 30, 2018

Our History

https://www.curieuseshistoires.net/victoria-montou-esclave-revolte/

https://www.albany.edu/faculty/jhobson/middle_passages/warrior_women/next.html

https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=fr&u=http://www.haiticulture.ch/Defilee.html&prev=search

http://www.voicesfromhaiti.com/tag/marie-sainte-dedee-bazile/

https://jafrikayiti.com/roots-of-black-lives-matter-in-bwa-kay-iman-haiti-14-15-august-1791/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Israel%E2%80%93South_Africa_relations#Relations_between_Israel_and_post-apartheid_South_Africa

http://mondoweiss.net/2013/12/alliance-relationship-apartheid/

http://www.voicesfromhaiti.com/tag/marie-sainte-dedee-bazile/

http://www.angelfire.com/la2/prophet1/fwcontents.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20040407084623/http://www.viewfromthewall.com/

https://www.amazon.com/Final-Warning-History-World-Order/dp/1615779299

http://www.evangelicaltruth.com/freemasonry-html

http://www.texasstandard.org/stories/texas-exhibit-refuses-to-forget-one-of-the-worst-periods-of-state-sanctioned-violence/

https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/sport/353289/jamaica-make-netball-history-beating-nz-59-53

http://dailydsports.com/jackie-joyner-kersee/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/1873-colfax-massacre-crippled-reconstruction-180958746/

Wednesday, March 21, 2018

More on African American history

Remembering Marielle Franco

https://theintercept.com/2018/03/19/just-as-u-s-media-does-with-mlk-brazils-media-now-trying-to-whitewash-and-exploit-marielle-francos-political-radicalism/

https://jacobinmag.com/2018/03/marielle-franco-brazil-assassination-police

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/a-black-female-politician-was-gunned-down-in-rio-now-shes-a-global-symbol/2018/03/19/98483cba-291f-11e8-a227-fd2b009466bc_story.html?utm_term=.59fb618e085f

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marielle_Franco

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/mar/19/marielle-franco-brazilian-political-activist-black-gay-single-mother-fearless-fighter-murder

Tuesday, March 20, 2018

Facts.

https://www.vox.com/2015/7/16/8978257/ida-b-wells

https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Ida_B._Wells

https://www.vox.com/cards/things-about-isis-you-need-to-know/sunni-shia-conflict-ISIS

https://socialistworker.org/2018/03/20/the-us-war-machine-unleashed-in-iraq

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Burnett_Talbert

http://www.ritualabusefree.org/Christian%20Worker's%20Handbook.htm#B2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abolitionism

Monday, March 19, 2018

Tuesday, March 13, 2018

More Information

http://maimounayoussef.com/#about

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/05/13/406243272/im-from-philly-30-years-later-im-still-trying-to-make-sense-of-the-move-bombing

https://www.theroot.com/alabama-sheriff-pocketed-extra-money-from-jailhouse-foo-1823738132

https://www.scribd.com/document/373201484/The-City-of-Baltimore

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/former-black-panther-herman-wallace-dies-days-after-judge-overturns-murder-conviction-that-saw-him-8859711.html

https://www.refinery29.com/2017/02/141616/famous-black-women-in-stem

https://www.google.com/search?q=famous+african+american+woman+scientist&oq=famous+african+american+woman+scientist&aqs=chrome..69i57j0.6160j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/05/13/406243272/im-from-philly-30-years-later-im-still-trying-to-make-sense-of-the-move-bombing

https://www.theroot.com/alabama-sheriff-pocketed-extra-money-from-jailhouse-foo-1823738132

https://www.scribd.com/document/373201484/The-City-of-Baltimore

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/former-black-panther-herman-wallace-dies-days-after-judge-overturns-murder-conviction-that-saw-him-8859711.html

https://www.refinery29.com/2017/02/141616/famous-black-women-in-stem

https://www.google.com/search?q=famous+african+american+woman+scientist&oq=famous+african+american+woman+scientist&aqs=chrome..69i57j0.6160j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

Saturday, March 10, 2018

Culture

http://afam.ucla.edu/faculty/jemima-pierre/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylicia_Rashad

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Columbian_era

http://maimounayoussef.com/

https://blavity.com/josephine-baker-fled-americas-racism-to-dance-sing-and-become-a-spy?_medium=facebook&utm_campaign=tz&utm_source=zulu

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fxy6ZaMOq8

This is the link.

http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-212

https://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/1968/reference/timeline.html

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/timeline-seismic-180967503/

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-nra-is-losing

http://time.com/81573/how-to-live-longer/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylicia_Rashad

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Columbian_era

http://maimounayoussef.com/

https://blavity.com/josephine-baker-fled-americas-racism-to-dance-sing-and-become-a-spy?_medium=facebook&utm_campaign=tz&utm_source=zulu

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8fxy6ZaMOq8

This is the link.

http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-212

https://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/1968/reference/timeline.html

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/timeline-seismic-180967503/

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-nra-is-losing

http://time.com/81573/how-to-live-longer/

Friday, March 09, 2018

Remembering the Vietnam War

https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/09/21/ideology-as-history-a-critical-commentary-on-burns-and-novicks-the-vietnam-war/

https://popularresistance.org/trumdcare-is-dead-single-payer-is-the-only-real-answer-says-medicare-architect/

http://www.demos.org/blog/1/15/18/trump-v-mlk-rising-american-demos-supports-all-dreamers

http://www.gafollowers.com/things-your-school-didnt-teach-about-martin-luther-king/

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/lbjs-last-interview

https://kennedysandking.com/reviews/ken-burns-lynn-novick-the-vietnam-war-part-three-the-johnson-years

https://kennedysandking.com/reviews/ken-burns-lynn-novick-the-vietnam-war-part-four-the-nixon-years

https://kennedysandking.com/videos-and-interviews/the-vietnam-war-and-the-destruction-of-jfk-s-foreign-policy

https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/09/21/ideology-as-history-a-critical-commentary-on-burns-and-novicks-the-vietnam-war/

Wednesday, March 07, 2018

Tuesday, March 06, 2018

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman

She was a heroine, who fought for our ancestors' rightful freedom. Throughout her life, she brought down tremendous barriers and possessed courage plus strength. Always an advocate for justice, Harriet Tubman gravitated her actions in the cause of social justice in order for real social change to transpire. She was born in the Eastern Shore region of Maryland. Not only did she escaped slavery into freedom audaciously. She freed many of her own family members plus hundreds of other black human beings from bondage. Harriet Tubman was a leader of the Underground Railroad, which was a network of pathways, varied routes, and safe houses that helped thousands of black human beings to escape the tyranny of slavery. People of diverse colors and creeds were active participants in the Underground Railroad too. As a humanitarian and an abolitionist, Harriet Tubman display an excellent amount of human compassion and personal conviction. Threats against her life and posters of rewards (from racist southern slave owners) for her capture didn't deter her at all. She persisted onward as a heroine of the ages. Tubman fought for the Union during the U.S. Civil War by spying and leading a raid (called the Combachee Raid on July 2, 1863. Colonel James Montgomery was part of it as well. Afterwards, more than 750 black people were freed. Many of them joined the Union Army) to defeat the Confederate, traitorous enemy. After the American Civil War, she continued to advocate for equality and suffrage (or giving women the right to vote). Harriet Tubman lived a long life into the early 20th century. Constantly fighting for freedom, Harriet Tubman exemplified greatness and forthright, glorious consciousness. She risked her life for us. We owe a lot to her activism, her tenacity, and her indispensable sacrifice. Therefore, it is time for everyone to give Harriet Tubman even a greater amount of credit including gratitude for her actions of valor and her unconditional love for black people.

Early Life

Harriet Tubman was born in ca. 1822 in Dorchester County, Maryland. Her original name was Araminta Ross. Her parents were slaves too. Their names were Harriet Green and Ben Ross. Rit was oppressed by Mary Pattison Brodess (and later her son Edward). Ben was oppressed by Anthony Thompson, who was Mary's second husband. Mary and Anthony ran a plantation near Blackwater River in Madison, Maryland. Also, Tubman's maternal grandmother arrived into America on a slave ship from Africa. She was told that she was of Ashanti lineage (which is found in Ghana. There is no evidence to confirm or deny the assertion). Harriet Tubman's mother, Rit, was a cook for the Brodess family. Ben was a skilled woodsman. He managed the timber work on Thompson's plantation. Rit and Ben married in ca. 1808. They had nine children together according to court records. Their names are: Linah, Mariah, Ritty, Soph, Robert, Minty (Harriet), Ben, Rachel, Henry, and Moses. Slavery threatened to split the family apart. Edward Brodess sold three of Rit's daughters and one son (Linah, Mariah, Ritty, and Soph). They were separated from the family permanently. One trader from Georgia wanted Brodess to buy Rit's youngest son, Moses. So, Harriet Tubman hid Moses for a month. She was assisted by other slaves and free black people in the community. Harriet Tubman confronted the slave owners about the sale. When Brodess and the Georgia man came into the slave quarters to try to seize the child, something happened. Rit told them, "You are after my son; but the first man that comes into my house, I will split his head open." Then, Brodess backed away and didn't participate in the sale. This even influenced Tubman's resistance mentality according to her biographers.

Tubman's mother worked in the "big house." She struggled to find time for her family. Tubman took care of a younger brother and baby. Harriet Tubman worked for a woman named Miss Susan when she was five or six years old. She was a nursemaid. She took care of a baby. She was lashed five times before breakfast on one day. She had those scars for the rest of her life. She resisted by running away for five days. Harriet Tubman fought back and wore layers of clothing to protect herself from the beatings. She also worked for a planter named James Cook. She checked the muskrat traps in marshes. She had the measles. She was so sick that she went to the Brodess and her mother healed her. As she became older, she did field and forest work. She drove oxen, plowed, and hauled logs. She was illiterate as a child. She believed in God and in the deliverance sections of the Old Testament. She was inspired by spirituality throughout her life.

She was beaten constantly by slave owners in Dorchester County, Maryland. She was hit in the head when she was hit by a heavy metal weight. That injury caused her to have epileptic seizures, headaches, visions, and dream experiences. This existed throughout her life. This occurred after one time, the adolescent Tubman was sent to a dry goods store for supplies. She saw a slave owned by another family, who had left the fields without permission. His overseer wanted her to help restrain the slave. She refused. The slave ran away. The overseer threw a 2 pound weight at him. It struck her. Her hair saved her life. She was unconscious and bleeding. She had no medical care for 2 days. It was a miracle that she survived. She was sent back to the fields. She had blood and sweat on her face. Some believe that she had temporal lobe epilepsy as a product from the injury. She had seizures and many like minded episodes.

Escape from Slavery

On 1840, Tubman's father (or Ben) was manumitted from slavery at the age of 45. This was stipulated in a former owner's will. His actual age was closer to 55. He worked as a timber estimator and foreman for the Thompson family. Years later, Tubman used a white attorney to investigate her mother's legal status. He was paid 5 dollars. The lawyer found that a former owner had issued instructions that Rit like her husband would be manumitted by 45 years old. The record showed a similar provision to Rit's children and any children born after she reached 45 years old age were legally free. The Pattison and Brodess families ignored this document. Tubman wanted to free her family. At 1844, Harriet Tubman married a free black man. His name was John Tubman. It was a complicated union since Tubman was once a slave during this time. Blended marriage of free people of color marrying enslaved people were common in the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Half of the black population in that region was free. Most African American families had both free and enslaved members. Tubman changed her name from Arminta to Harriet after her marriage. She might have adopted her mother's name out of religious conversion or to honor another relative.

Harriet Tubman was ill again in 1849. Edward Brodess tried to sell her, but no one would buy her. She was angry at slavery and her family suffering. So, Tubman Harriet Tubman prayed for the owner to change his ways. She said later: "I prayed all night long for my master till the first of March; and all the time he was bringing people to look at me, and trying to sell me." When it appeared as though a sale was being concluded, "I changed my prayer," she said. "First of March I began to pray, 'Oh Lord, if you ain't never going to change that man's heart, kill him, Lord, and take him out of the way." A week later, Brodess died, and Tubman expressed regret for her earlier sentiments. Brodess's death could have increased the likelihood that Tubman would be sold and her family broken apart. His widow was Eliza. Eliza worked to sell the family's slaves. Then, Tubman decided to escape. She didn't wait for Eliza to continue evil any longer among her and her family. "[T]here was one of two things I had a right to," she explained later, "liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other." Tubman was hired out to Dr. Anthony Thompson. He owned a large plantation in Popular Neck in neighboring Caroline County. On September 17, 1849, Tubman (and her brothers Ben and Henry) escaped from slavery. Eliza didn't realize her escape for a time, because the slaves were hired out for some time. Eliza posted a runaway notice in the Cambridge Democrat. Eliza offered 100 dollars for each slave returned. Tubman's brothers had second thoughts in the beginning. Ben may have just became a father. The 2 men went back. Tubman returned with them.

Later, Tubman escaped again. She left without her brothers. She tried to tell her mother of her plans. She sang a coded song to Mary, a trusted fellow slave, that was a farewell. "I'll meet you in the morning," she intoned, "I'm bound for the promised land." Harriet Tubman used the Underground Railroad to help her travel into the North. The Underground Railroad was made up of organized system of free and enslaved black people plus abolitionists including other activists. One large member of the network were the Religious Society of Friends or Quakers. The Preston area near Poplar Neck in Caroline County contained a substantial Quaker community and was probably an important first stop during Tubman's escape. She took a route northeast along the Choptank River via Delaware and then north into Pennsylvania. She traveled almost 90 miles. She walked by foot. This took from 5 days to three weeks. She used the North Star to travel by night. She avoided slave catchers. The conductors of the Underground Railroad were very successful. Tubman traveled into a friendly house and hid in many locales. She knew of the land. She was happy to reach Pennsylvania. She said that it felt like Heaven to be free.

She was called Moses by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison because of her courageous actions. Moses was from the story of Exodus who freed Hebrews from slavery in ancient Egypt She worked in Maryland to rescue people. Moses was used in code via songs like Go Down Moses to signal her act to free her people. She changed the tempo of singing to mention whether it was either safe or too dangerous. Go Down Moses song was sung by black regiments during the Civil War and it's song today to pay tribute to Tubman and to various struggles for freedom.

Harriet Tubman traveled into Philadelphia. She missed her father, mother, brothers, and sisters. She saved money by working jobs. The evil Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 wanted to punished slaves who escaped. It funded law enforcement to kidnap black people. Many black people sought refuse in Southern Ontario. Ontario banned slavery by that time. In Philadelphia, many poor Irish immigrants competed with free black people for work increasing racial tensions. On December 1850, Harriet Tubman was told something. It was about her niece Kessiah and her two children (6 year old James Alfred and baby Araminta) about to be sold in Cambridge. She came into action to stop this. She came into Baltimore where her brother in law Tom Tubman hid her until the sale. Kessiah's husband was a free black man named John Bowley. Bowley, Kessiah, and their children escaped into a nearby safe house. By night, Bowley sailed the family to Baltimore where they met Tubman. Tubman brought the family to Philadelphia. During the next spring, Harriet Tubman helped to free her other family members. During this second trip, Tubman found her brother Moses and 2 other men. She might have worked with the Quaker Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware. He was an abolitionist. She was more confident with each trip and her family knew of her heroism. She worked with many people. She said in 1897 (in an interview with Wilbur Siebert) that she stayed with many black and white people like ministers, activists, and families to help free people.

She came back into Dorchester County in the fall of 1851. She wanted to find her husband John. Yet, John was married to another woman named Caroline. John wanted to stay put. She freed more slaves and led them to Philadelphia. John and Caroline lived together and John was killed 16 years later in an argument with a white man named Robert Vincent. Many slaves went into Southern Ontario because of the Fugitive Slave act made it more difficult for black people in the North. She led others to escape slavery in December 1851. They could have stopped in the home of Frederick Douglass as his third autobiography mentioned 11 people at his house before. Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass admired each other a great deal. Harriet Tubman freed more people in the Eastern Shore of Maryland. She freed her brothers Henry, Ben and Robert (plus their wives and children). She worked in the winter. She used spirituals in coded messages to help those to freedom. She carried a revolver to defend herself. She didn't allow others to go back. Harriet Tubman was never captured. Years later, she told an audience: "I was conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say – I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger." She led many of her relatives into Ontario, Canada.

Harriet Tubman's Continued Activism

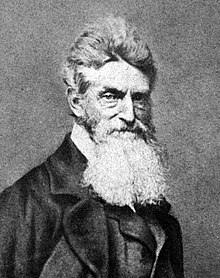

By April of 1858, Tubman met abolitionist John Brown. Brown wanted to use self defense and violence to end slavery in America. She didn't agree with violence against whites, but she agreed with the goal of ending slavery in America. Both of them believed that God told them to fight the evil of slavery. She said that she had a prophetic vision of meeting Brown before their encounter. Brown wanted to attack Harpers Ferry to get people to organize a revolt against slavery. She called her General Tubman. She knew of networks and resources in the border states of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware. Brown wanted her expertise. Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison didn't agree with the Harpers Ferry raid. Tubman organized former slaves to meet with John Brown. John Brown had a meeting in Chatham, Ontario to show his plan for the raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia on May 8, 1858. Brown put the act on hold when the government knew of his plans. Tubman aided him in the effort. Tubman spoke to abolitionist audiences and helping her relatives. Brown prepared for the attack. October 16, 1859 was when the raid took place. Tubman wasn't there. The raid failed and Brown was hanged as a martyr. He was hanged in December 1859. Tubman praised John Brown as a hero. In early 1859, abolitionist Republican U.S. Senator William H. Seward sold Tubman land near Auburn, New York for $1,200. The city was where antislavery activism was real. She was friends with many people in the area. Her relatives lived in Auburn too. Later, Harriet returned back from Maryland with her niece and a young black girl named Margaret. November 1860 was the time of her last rescue mission. She rescued sister Rachels' two children Ben and Angerine. Rachel died. They lived in the home of David and Martha Wright in Auburn, New York on December 28, 1860.

The American Civil War

During the American Civil War, Harriet Tubman worked with the Union to end slavery. General Benjamin Butler aided escaped slavery coming into Fort Monroe. Tubman worked with Union abolitionists in Boston and Philadelphia. She worked in Port Royal, South Carolina with black newly freed people. She worked with abolitionist General David Hunter. Hunter organized black regiments. Abraham Lincoln reprimanded Hunter for his actions and Tubman criticized Lincoln. She helped aiding soldiers in Port Royal. She scouted areas and used her efforts to aid the Combahee River Raid. That was in South Carolina. She helped to liberate black men, women, and children. That was when Tubman was the first woman to lead an armed assault during the Civil War. Montgomery was involved too. It happened on June 2, 1863. She knew of the land, because the marshes and rivers in South Carolina were similar to those of the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The raid freed more than 750 slaves. Newspapers praised Tubman's energy, patriotism, and integrity. She worked with Colonel Robert Gould Shaw at the assault on Fort Wagner. This event was shown in the film Glory. She worked with intelligence alongside with Colonel James Montgomery and gave intelligence that aided the capture of Jacksonville, Florida. Tubman worked for the Union continuously. She liberated slaves and nursed the wounded soldiers in Virginia. She cared for her parents too. The Confederacy surrendered on April of 1865. Tubman went home to Auburn, New York.

Later Life

She was assaulted in a train ride to New York. The conductor wanted her to go into the smoking car. She refused as she worked for the government. He cursed at her. He grabbed her and she defended herself as she had every right to do. He called 2 other passengers for help. She clutched at the railing. The men broke her arm at the railing. They threw her in the smoking car causing her more injuries. She was cursed at by more white passengers and some wanted her to leave the train. She wasn't paid a regularly salary. She was denied compensation. She was disrespected by racists. Her family was in poverty and she had difficulties in getting wealth. She lived in Auburn, New York. Nelson Charles Davis helped Tubman. He was 5 foot 11 inch tall. He was the veteran of the 8th United States Colored Infantry. He was 22 younger than her, but they fell in love and married on March 18, 1869. They wed at the Central Presbyterian Church. They adopted a baby girl Gertie in 1874 and the lived as a family. Nelson died of tuberculosis on October 14, 1888. Sarah Hopkins Bradford (who admired Tubman) wrote an authorized biography entitled Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman. The 132-page volume was published in 1869, and brought Tubman some US$1,200 in revenue. She wrote Harriet, the Moses of her People in 1886. Tubman faced debts. It would be until 1899 that the government increased Tubman's pension after she petitioned Congress to do so in 1898. She promoted women's suffrage or women having the right to vote. She promoted equality. She traveled into New York, Boston, and Washington D.C. to promote women voting rights.

She spoke at the first meeting of the National Federation of Afro-American Women in 1896. She worked in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Auburn in 1903. She donated land to the church. She wanted to helped elderly black people. The Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged opened on June 23, 1908. She had brain surgery to deal with the seizures. By 1911, her body became frail. She died of pneumonia in 1913. She was surrounded by friends and family. Just before she died, she told those in the room: "I go to prepare a place for you." She was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York.

Her Legacy

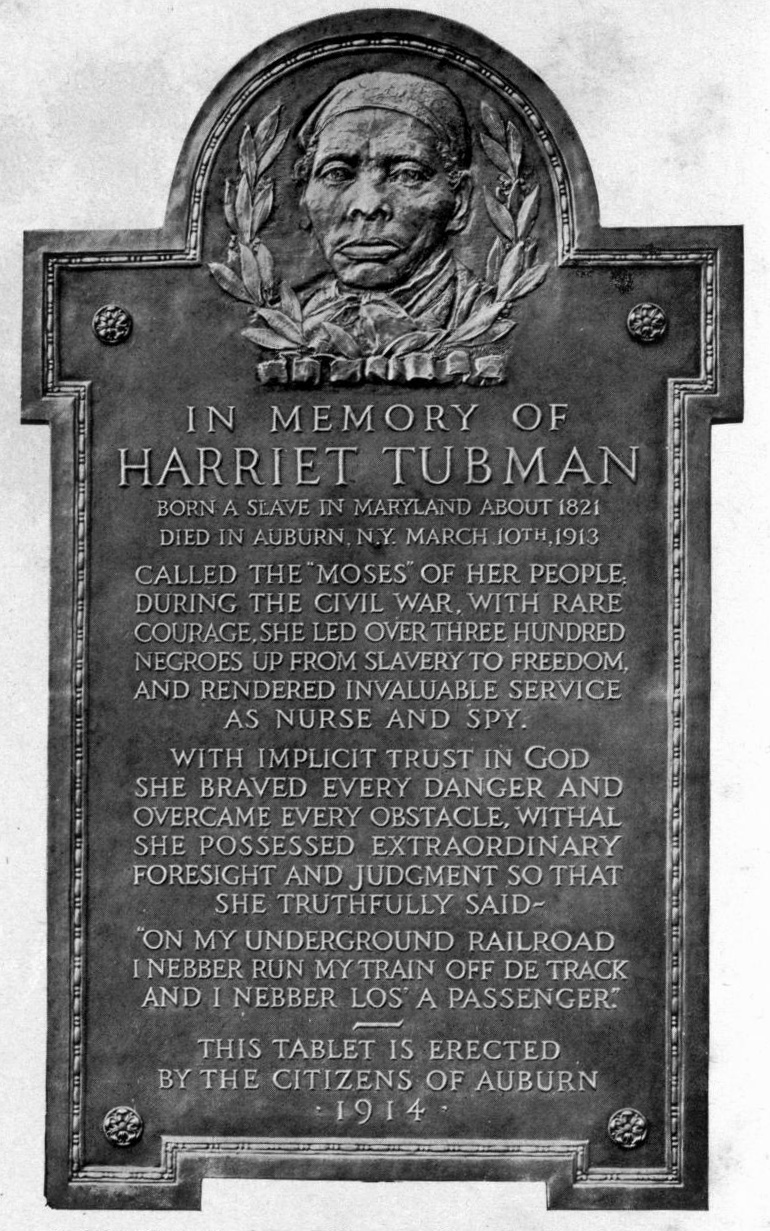

She inspired African Americans who desired equality and civil rights. She has been by people of all races as a heroic black woman and people from across the political spectrum respect her a great deal. The city of Auburn displayed a commemorative plaque erected in 1914 that celebrated the achievements of Sister Harriet Tubman. She was a hero. The Harriet Tubman home is now a museum and educational center. By March of 2013, President Barack Obama signed a proclamation creating the Underground Railroad National Monument on the Eastern Shore. Harriet Tubman was posthumously inducted into the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame. Today, we honor her heroism and sacrifice for us.

By Timothy

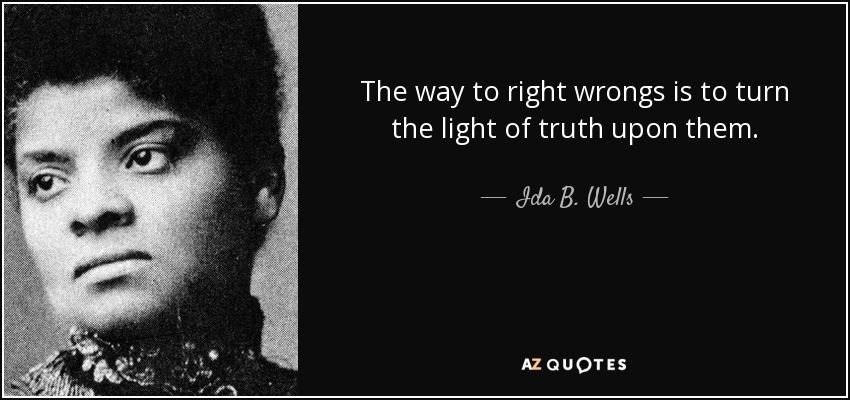

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells

Defender of black human life, lover of truth, and constant social activist are accurate phrases which define the courageous life of the civil rights leader Ida B. Wells. Ida B. Wells was born in 1862 during the Civil War in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her parents were active in the fight for freedom during Reconstruction. Her mother was religious and her father fought for the liberation of black people constantly. She faced a lot from threats and racism, but those evils never stopped her from establishing profound excellence. Fisk University and Shaw University were locations where she was educated at. Subsequently, Ida B. Wells became a great newspaper editor and an expert sociologist. She worked in the South at Memphis, Tennessee as a means for her to be an activist, a journalist, and a scholar. She overtly fought lynchings. Additionally, Ida B. Wells allied with W.E.B. Du Bois and Frederick Douglass on many endeavors. Ida B. Wells was one of the numerous founders of the NAACP (or the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) during the early 20th century. Ida B. Wells wanted to give the world the formidable voice of Black America. As a traveler internationally, she formed women organizations and believed in the Dream of human justice. She greatly defended the lives of black men who were falsely accused of raping white women. Subsequently, she defended the humanity, the autonomy, and the dignity of black women. She was a beautiful black woman who demanded real change. Ida B. Wells had four children and cared deeply for her family. Speaking up for the human rights of black people was definitely part of her life's work. Ida B. Wells came into Chicago as a way for her to continue in the progressive cause of social liberation for black people. She lived in the era of Jim Crow and during the epidemic of the lynching of black men, black women, and black children. Ida B. Wells was involved in politics too and she wholeheartedly believed in women's suffrage. An inspiration to black women and black people in general, Ida B. Wells always was committed to the premise of human justice for all. Ida B. Wells gave us the gift of activism in comprehensive ways.

Her Early Life

To begin with, Ida B. Wells was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi on July 16 1862. She was born a slave along with her parents. Her parents were James Wells and Elizabeth Wells. They were enslaved by Spires Bolling, who was an architect. They lived in the Bolling’s house. She was born months before the Lincoln Emancipation Proclamation, which banned slavery in Confederate held lands. After the Civil War, Ida B. Wells’ father became more overt in fighting for the justice for the black community. He was involved in politics and was a member of the Loyal League. He came into Shaw University in Holy Springs. The University is now called Rust College. He gave speeches and supported black candidates during Reconstruction. He never ran for office himself. Elizabeth Wells was a religious woman who helped her children a great deal. Both of Ida B. Wells’ parents were involved in Republican politics during Reconstruction, because back then tons of Republicans opposed racial injustice. Ida B. Wells attended Shaw University for a while. Tragedy struck in 1878. That was when her parents died because of a yellow fever epidemic in Holly Springs. Her infant brother named Stanley died too. Ida was just 16 years old when these sad events occurred. Ida and her siblings were orphaned. Many men were a father figure to her like Alfred Froman, Theodore W. Lott, and Josiah T. Settle. She lived with Settle in 1886 and 1887. Some relatives wanted Ida and her relatives to be split in foster care homes, but Ida B. Wells was adamantly opposed to this. Ida B. Wells went to the funerals of her parents and her brother. Later, she lived with her younger siblings as a family. She worked as a teacher in a black elementary school in Mississippi. Her siblings were cared for by friends and relatives while Wells was away teaching. She received money to help her family. Peggy Wells or her paternal grandmother cared for her siblings too. Wells didn’t like earning only $30 a month as compared to $80 a month in segregated schools. She opposed discrimination and wanted to improve the education of black people. In 1883, Ida B. Wells moved into Memphis, Tennessee with her three younger siblings. They lived with their aunt and other family members. She taught there too. She was part of the Shelby County school system in Woodstock. During the summer, she attended summers sessions at Fisk University. Fisk University is a historically black college in Nashville. A historical black college in Memphis named Lemoyne-Owen College was another college that she attended too. Ida B. Wells believed in justice for black people and women’s rights.

This is Ida B. Wells with the widow of Tom Moss.

Social Activism

The time of May 4, 1884 would change her life forever. That was the date when Ida B. Wells was in the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. A train conduct wanted her to give up her seat in the first class ladies car. He wanted to move her to the smoking car, which was crowded with other people. She refused to do so. The railroad authorities kicked her off the train. By 1883, the Supreme Court ruled against the federal Civil Rights Act of 1875 (which banned racial discrimination in public accommodations). Racially segregated railroad companies segregated their passengers. Wells wrote of her experience in the black church weekly newspaper article found in The Living Way. She hired an African American attorney to sue the railroad. That attorney was paid off by the railroad. So, she hired a white attorney. She won her case on December 24, 1884. The local circuit court granted her a $500 award. Then, the railroad company appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which reversed the lower court’s ruling in 1887. Wells was ordered to pay the costs. She was disappointed and said, “I felt so disappointed because I had hoped such great things from my suit for my people...O God, is there no...justice in this land for us?" She continued to teach an elementary school class. During that time, she was offered an editorial position for the Evening Star in Washington, D.C. She also wrote for The Living Way weekly newspaper. It was done under her pen name “Iola.” She wrote about racial issues. She was the co-owner and editor of Free Speech and Headlight, which was an anti-segregation newspaper. It was started by Reverend Taylor Nightingale being based at the Beale Street Baptist Church in Memphis. She criticized racism and oppression. So, the Memphis Board of Education dismissed her. She was devastated. Yet, she moved on and used her energy to write articles for The Living Way, the Free Speech, and Headlight. Thomas Moss was Wells’ friend. In 1889, he opened a Peoples Grocery. It was found in the Curve. That was a black neighborhood just outside the Memphis limits. It did well. It also competed with a white owned grocery store across the street. By 1892, a white mob invaded his store. It was an altercation where three white men were shot and injured. Ida B. Wells was in Natchez, Mississippi when this occurred. Moss, McDowell, and Stewart were arrested and jail. A white lynch mob stormed the jail. They killed the three men. They were lynched. Ida B. Wells later called for all black people to leave Memphis because of the racist violence against black people. She wrote of these words in Free Speech and Headlight. She exposed lynching. More than 6,000 black people left Memphis. Other people boycotted white owned businesses. Ida B. Wells bought a pistol to protect herself. She later wrote, "They had made me an exile and threatened my life for hinting at the truth." She used investigative journalism to find out that lynching existed because of racism, jealousy of black progress, and a tactic by racists to harm the economics of the black community. She started her own anti-lynching campaign during the late 1800’s. She spoke in black women’s clubs and raised more than $500 to investigate lynchings and publish her results.

She found that white racists used the lie that every black person was raping white women as an excuse to lynch black people. She exposed American white masses of people being silent on this atrocity of lynching. She published her findings in a pamphlet entitled, “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” She wrote an editorial and came into New England from Memphis. She covered another story for a newspaper. White people in the newspapers The Daily Commercial and the Evening Scimitar hated Ida B. Wells. More studies proved that Wells’ finding were right. They found that lynching was used as a way to harm and control the black community. Economics played a role in the sense that white racist jealous of black progress contributed to lynching. The scholar Oliver C. Cox defined lynching in his 1945 article entitled, “Lynching and the Status Quo.” Ida B. Wells continued to speak out against lynching in New York City and other places among African American women. Victoria Earle Matthews and Maritcha Remond Lyons (who were political activists and clubwomen) raised funds for Wells’ anti-lynching campaign. These women were at the October 5, 1892 testimonial of Wells at Lyric Hall. Black women organized political activism in the Women’s Loyal Union of New York and Brooklyn. Ida B. Wells left Memphis and came into Chicago because her life was threatened. She wrote against lynching and wrote articles against it too. The New York Age newspaper published her articles. She investigated lynching incidents and the causes. She allied with Frederick Douglass and other black leaders to boycott the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The reason was that it lacked powerful images of African American life and refused to work with the black community. Articles about this reality were written by Wells, Douglass, Irvin Garland Penn, and Ferdinand Lee Barnett (or Ida B. Wells’ husband) in a pamphlet. It was entitled, “Reasons Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition." The pamphlet was distributed at the exposition too. The pamphlet showed the contributions of African Americans and exposed the evils of Southern lynchings. Wells told Albion W. Tourgee that 20,000 people received copies of the pamphlet at the fair. Ida B. Wells stayed in Chicago. She worked with the oldest African American newspaper in the city called the Chicago Conservator. Wells by 1893 thought about suing two black Memphis attorneys for libel. She lacked money and Tourgee couldn’t afford to help. Ferdinand Barnett accepted the pro bono job to do it.

Her Family and Continuing in the Fight against Lynching

Ida B. Wells had many children in four. She married attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett in 1895. She kept a diary too. He had 2 children from a previous marriage as he was a widower. His sons are Ferdinand and Albert. They had four children together. Their names are Charles, Herman, Ida, and Alfreda. She traveled the world and took care of her children too. She toured Europe to fight lynching. Many English people supported her cause. She toured Europe in 1893 and in 1894. Catherine Impey supported her. Impey was a British Quaker, an opponent of imperialism, and believer in racial equality. Thousands of people came to see her. Many Europeans were shocked at the brutality against black people via lynching in America. Ida B. Wells showed crowds of an image of black people being lynched. She raised money. By 1894, she toured Great Britain. William Penn Nixon was the editor of the Daily Inter-Ocean. That was a Republican newspaper in Chicago. It was the only major white paper that persistently denounced lynching. After she told Nixon about her planned tour, he asked her to write for the newspaper while in England. She was the first African-American woman to be a paid correspondent for a mainstream white newspaper (Tourgée had been writing a column for the same paper). Her article "In Pembroke Chapel" recounted the mental journey that an English minister had shared with her. The London Anti-Lynching Committee was created by Ida B. Wells to spread anti-lynching movements in Europe. C. F. Aked from England read about the Miller lynching in Bardwell, KY and supported Wells. Many white feminists aback then were racist. Willard was a white feminist who had black friends, but she made racist comments blaming black people for the defeat of the temperance legislation (that banned people from drinking alcohol). She was a member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union or the WCTU. Frances Willard was president of the group from 1879 to 1898. Ida B. Wells accused Willard of downplaying lynching and allowed Southern branches of the WCTU to segregate and prevent black women from joining. Wells was right. Wells stood her ground despite being slandered by some in the New York Times. Her 1895 pamphlet A Red Record outlined her differences with Willard. Wells' British tour ultimately led to the formation of the British Anti-Lynching Committee, which included prominent members such as the Duke of Argyll, the Archbishop of Canterbury, members of Parliament, and the editors of The Manchester Guardian. Ida B. Wells’ Southern Horrors pamphlet documented lynching.

The South in Mississippi, and other states banned black people form voting via literacy test, poll taxes, etc. Many poor white people were restricted to vote too, but black people experienced Jim Crow in a harsh fashion. Ida B. Wells-Barnett also wanted black people to use arms to defend themselves against lynching. Self defense is a human right. Self preservation is a human right too. Wells-Barnett published The Red Record (1895), a 100-page pamphlet describing lynching in the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. It also covered black peoples' struggles in the South since the Civil War. Lynching was huge from 1880 to 1930 (and afterwards). Frederick Douglas wrote about lynching during the days of slavery, the Reconstruction Era, and afterwards too. Lynching was done to promote white supremacy, but black people rose up to fight against such evils. W.E.B. Du Bois worked with Ida B. Wells. Each helped to found the NAACP. Du Bois said that Wells chose not to be included from the original list of founders of the NAACP while Wells said that Du Bois deliberately excluded her from the list. She formed a Republican Women’s Club in Illinois to fight for women to have the right to vote and hold office. The club supported Lucy L. Flower and Flower was elected as Trustee of the University of Illinois. Frederick Douglass praised her work. He said, “You have done your people and mine a service...What a revelation of existing conditions your writing has been for me.”

Her Later Years

In 1896, she founded the National Association of Colored Women’s clubs and the National Afro-American Council. She worked during the time of Mary Church Terrell’s activism too. Wells wanted to improve the lives of black people in Chicago. The Great Migration started and black people competed for jobs and resources alongside immigrant Europeans. Ida B. Wells worked in urban reform in Chicago during the last 30 years of her life. She wrote her autobiography during her retirement. It is entitled, “Crusade for Justice’ in 1928. She never finished her book. She passed away of kidney failure on March 25, 1931. She was 68 years old. She was buried in the Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. The city later integrated the cemetery. She has been honored by many people among many organizations from the National Association of Black Journalists to the Ida B. Wells Memorial Foundation. The Ida B. Wells Museum has been established to protect, preserve and promote Wells’ legacy. There is the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum that celebrate her and African American history in her hometown of Holly Springs, Mississippi. Ida B. Wells Barnett was a legend.

Epilogue

Many words define the life of Sister Ida B. Wells including heroic and activism. Her life was a life of challenges and her using her will and activism to make changes in our society. She created a foundation whereby we would live in this society during this age of time. She believed in common unity among our people and she fought vigorously to end lynching once and for all. She refuted the lying stereotypes about black men and black people in general. She defended the rights of women as women having equality and justice is key for all people to have justice. During this time of the year, we are reminded of her sacrifice and her powerful legacy. She believed in hope and we do too. Her family was strong and she was the total definition of a strong black woman. Always a champion for freedom, she wrote articles for newspapers, she gave speeches worldwide to advance liberty, and she believed in defending her family including her community. She taught us many things. She taught us that in order to eliminate an evil, we must speak out against it and fight it. In a comprehensive fashion, we want black liberation and human liberation too. She nobly pursued greatness and enacted greatness helping the lives of many during her time and during future generations.

Rest in Power Sister Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

By Timothy

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)